Like the other listed CFD providers, CMC Markets has had a rocky couple of years on the stock market. Coming into the pandemic, the share prices of Plus500, IG, and CMC had all been crimped by ESMA’s marketing restrictions and caps on leverage, which came into play in late 2018.

Corona-induced volatility helped turn things around, as all three firms reported bumper profits and saw their share prices shoot upwards again. But calmer markets in 2021 led to further price declines. CMC is now trading about 70% above its pre-covid levels but less than half its April 2021 peak.

I have long thought that CFD providers make for good investments. They usually have a high return on capital, massive operating margins, no debt, and are highly cash generative. They also tend to make money in ‘normal’ years but do even better when there is more volatility, which arguably makes them something of a hedge against market crashes.

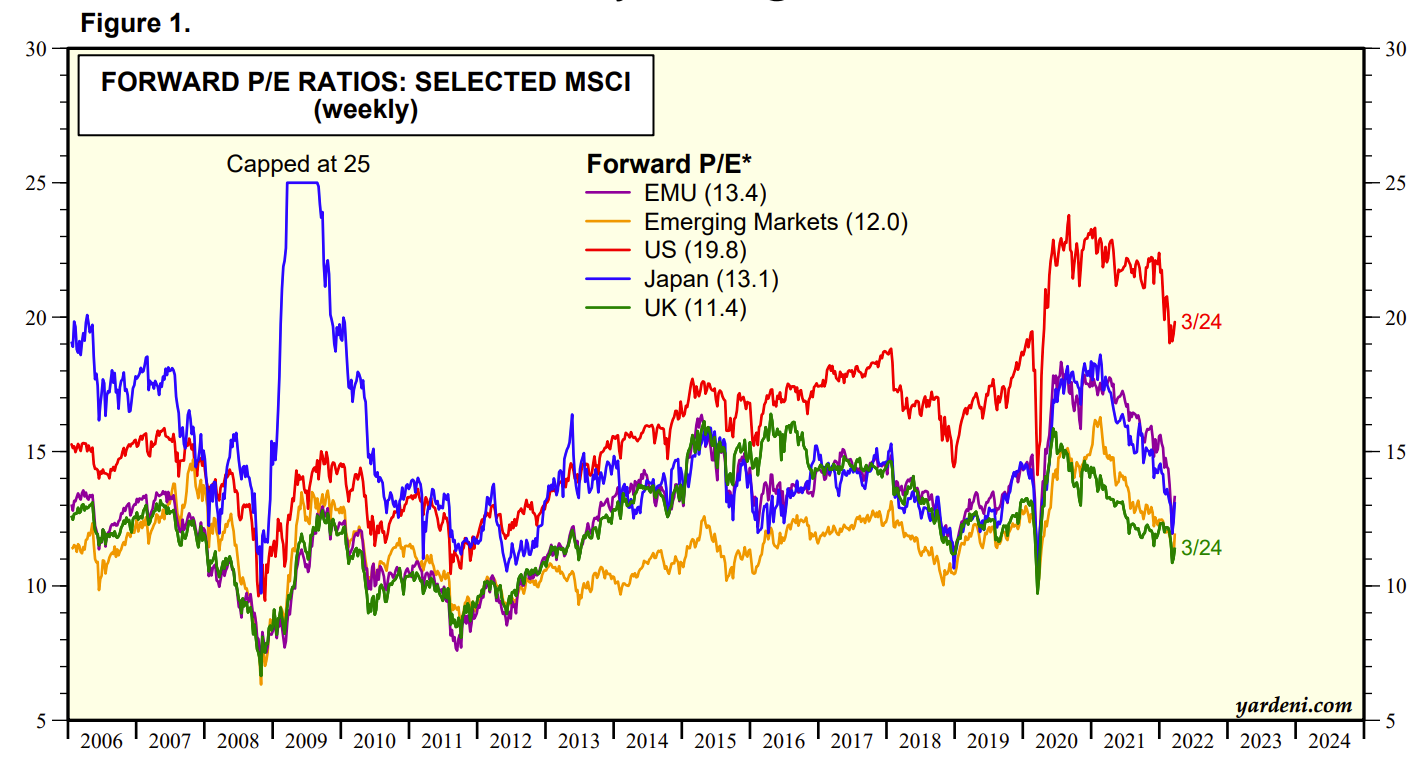

And yet market participants don’t seem to agree. All three of the companies mentioned above are now trading at below market average forward P/E ratios, which is pretty remarkable considering that the UK average is itself extremely low. That CMC has cash holdings equal to almost 25% of its current valuation, is arguably a sign of just how ‘cheap’ the company’s shares are.

There are three possible drivers for this:

- The UK market has been extremely sluggish since Brexit and still hasn’t recovered. You can see this in the chart below in forward P/E terms.

- There is probably still some fallout from ESMA. There is an argument to be made, which I don’t agree with, that leverage caps will hurt profitability.

- Market participants ignore the regular levels of profitability that these firms produce and instead try to ride the wave of profitability that volatility produces. When that wave comes crashing down, they get spooked and cash out.

In the case of CMC, I think an additional problem is the fact that founder and CEO Peter Cruddas – aka Lord Cruddas of Shoreditch (LCoS) – has a huge stake in the firm (more on this in a bit).

All of this has to be incredibly annoying. If you’re a public company, you want to be as valuable as possible. And if you are doing all the right things to get a higher valuation but not getting it, then after a while it’s got to be frustrating. Seen in that light, it shouldn’t be surprising that Plus500 is now looking to list in the US.

To be honest, I’d always thought CMC was probably more reasonably valued than its peers, mainly because it hasn’t grown as much. Even though the company produces impressive financials, low revenue and profit growth would not justify buying its shares at a high valuation.

What made me start to change my mind on this front was reading their 2021 results. As I wrote last week, CMC made 14% of their revenue (£54.8m) from stockbroking in 2021. This is more than IG Group makes and, I would imagine, any other CFD provider that offers share dealing today.

A couple of other points struck me in the report too.

One was that CMC is the….second biggest retail stockbroker in Australia? Ok, Australia is not the biggest market in the world but it’s still a decent-sized one. For me the more important thing is that:

- To become the second largest share dealing platform in a developed market is impressive.

- To reach that level you actually have to be doing something right and building a good product.

The other thing that amazed me was the size of the business. CMC has at least £40bn in assets under management. And that’s just in Australia. They’ve said they plan on launching in the UK this year. It will be a tough slog to get customers here but, as anyone who has heard LCoS shouting about ‘Project Tuna’ knows, they already have a relatively sophisticated client base for CFDs, so it will be interesting to see how quickly they can expand.

Even if it does take a while, that £40bn figure is worth thinking about for other reasons. Around the time CMC was publishing its 2021 results, asset manager Abrdn announced they would be buying Interactive Investor, a UK stockbroking platform, for £1.5bn.

At the time of the acquisition, Interactive had assets under management (AUM) of £55bn. In December 2020 that number was £38bn, which is less than CMC Markets has today.

AUM is not necessarily the best metric by which to judge a firm because companies will generate revenue from those assets in different ways. For instance, Interactive Investor made £73m in revenue back in 2018, when it only had £18bn in AUM. By comparison, CMC making £54.8m from £40bn looks less impressive.

On the other hand, keep in mind that CMC was previously making most of its money in share dealing from a white label agreement with Australian banking group ANZ. Those clients, all 500,000 of them, will now trade directly with CMC, after the company acquired them at the end of last year. Along with the UK expansion, we’ll have to wait and see if it can up the amount of money it makes from these customers.

Another good company to look at as a comparison, aside from Interactive Investors, is AJ Bell. For readers outside the UK, AJ Bell is a retail stockbroker based in Manchester.

In 2014, AJ Bell had £23.7bn in AUM and made £53.5m in revenue. Last year those figures rose to £72.8bn and £145.8m respectively.

AJ Bell also listed on the London Stock Exchange in 2018 and now has a market cap of £1.26bn.

There are two points worth considering here.

One is the potential of what CMC’s share dealing business could become. In 2014, AJ Bell made the same amount of money as CMC did, in nominal terms, with a much smaller level of AUM. But…

- CMC may be able to grow the amount of money it makes relative to its AUM. For example, it could switch on share lending or increase commissions.

- Even if it doesn’t do that, if it experienced similar growth in its AUM to AJ Bell then it could become a business worth hundreds of millions in the future.

The other point is to do with AJ Bell’s current valuation versus CMC’s. As noted, AJ Bell’s market cap is now £1.26bn. In comparison, CMC has a market cap of £736m.

This is despite the fact that CMC can make more money from its CFD business alone than AJ Bell does. Factor in CMC’s stockbroking business and it can feel like a bit of a head scratcher as to why the CFD provider is worth so much less than AJ Bell or, for that matter, Interactive Investor.

In other words, CMC’s stockbroking business alone arguably has the potential to be worth the same as AJ Bell or Interactive Investors. When you bolt on to that a very profitable CFD trading platform then it seems reasonable to say that CMC should be worth more.

There are probably a couple of reasons why that’s not the case.

One is that AJ Bell and Interactive Investors have both seen very impressive compound annual growth in their sales and profit numbers in the past decade. CMC has not done the same with its CFD business over the same time frame.

The other problem, which I alluded to earlier, is the dominance of LCoS in the CMC share register. LCoS and his wife own about 60% of CMC’s shares, which is probably unappealing to anyone that wants to buy with the intention of influencing the company (they won’t be able to) and means there may be problems down the line – what happens if LCoS decides to dump a load of shares at some point or, god forbid, he passes away and hands them over to someone that has no interest in CMC?

These points are valid but I would imagine it’s the former, which may be influencing investors the most.

This may be why CMC’s management team is mulling splitting the business in two. As I said last week, I think this is good from a business point of view, as the FX/CFD sector is so different to share dealing that it’s worth dividing them into two.

But it may also be good for creating more value for shareholders?

Share dealing is hot stuff at the moment, as the Interactive Investor deal goes to show. Look at Hargreaves Lansdown and AJ Bell, the two major publicly traded share dealing platforms in the UK, and you’ll also see that they’re trading at earnings multiples that are way above the market average. AJ Bell is trading at almost 30x estimated forward earnings per share. That’s a valuation which fits in US tech territory.

If CMC splits itself in two then it can:

- Cater to this enthusiasm

- Grow its share dealing business more visibly. Then it can say to analysts, ‘hey, look at how fast we’re growing’. And all those analysts will think it’s great they’re growing so much and they’ll give them buy recommendations and high price targets. Or that’s what CMC probably hopes will happen.

In contrast, CFDs are definitely not hot stuff. For whatever reason people just don’t seem to like them, probably for the reasons outlined earlier in this piece. So if you want to get a high stock market valuation you can (i) either do some more exciting stuff like CMC or (ii) get fed up with London and go to the US.

Whatever the case, I find the case for CMC compelling, so I’ve added them to my ISA. Please don’t blame me if you do the same and things go wrong.

LCoS book review

To continue on this week’s CMC theme, I spent the weekend before last cooped up at home with corona and so I read LCoS’s new autobiography, ‘Passport to Success: From Milkman to Mayfair’.

As the title suggests, the book is the story of LCoS’s life, from a council estate in East London to a billionaire business owner with a large mansion in Mayfair. LCoS wrote it in 90 days and, unusually, without the help of a ghostwriter.

There are some interesting tidbits and stories from his early childhood. For instance, LCoS dropped out of school at 15 as his family needed help paying the bills. One of his teachers was so distraught about this that he offered to pay LCoS to attend school. Sadly, his mother wouldn’t allow it as the family needed money. Had he stayed then he’d probably have gone on to study medicine. Under those circumstances it’s hard to imagine CMC coming into existence.

Beyond the travails of his youth, the book describes LCoS’s career and how CMC eventually came about. He started off working in the city for Western Union, sending messages on an old telex machine. When he was made redundant, he got a job in the foreign exchange trading team at International Marine Banking, a company that was eventually bought by HSBC.

CMC – originally ‘Currency Management Consultants’ – came about after LCoS got fed up with working for another bank. Originally the company was supposed to help businesses manage their exposure to FX forwards. But when that didn’t work, he moved into market making and broking, which is what he’d spent most of his career doing.

There are some amazing details of this journey. The one that sticks out most is the CMC IPO, when LCoS was listing his business on the stock exchange, not far from the same offices he’d helped his mum clean when he was a boy.

But for me, the most poignant part of the book is probably when LCoS talks about working for SCF Finance on their FX trading team. His boss was extremely well educated and had various degrees from prestigious universities. And yet over the years, LCoS continually trounced him when it came to making money from the markets.

This reminded me of a conversation I had once with someone that worked at Israel’s financial regulator. He’d been to perform a routine inspection at a derivatives trading firm and, as part of that, he had to speak with one of the head dealers.

Over the course of the conversation, it became apparent that the head dealer didn’t know what ‘derivatives’ were and also had no idea what ‘hedging’ was. The thing is, the person was amazing at their job and was making the firm a lot of money by trading derivatives and, one would imagine, hedging some of his risk.

This is not unusual. Trader-turned-author Nassim Taleb has written about how the most successful lumber trader in New York at one point in time thought that ‘green lumber’ was wood that had been painted green. In reality the ‘green’ is just a way of describing freshly cut lumber.

Similarly, Calouste Gulbenkian was very likely the wealthiest man in the world when he died in 1955. He made his money from oil but only visited a rig once, when he was 17, and was thought to understand very little about the practical side of production.

None of this is a negative, nor is it a sign of unintelligence. To the contrary, the big lesson from LCoS’s book for me is that practical knowledge triumphs over theory. CMC’s success is the result of real experience being put into practice, as opposed to highfalutin ‘educated’ theorists (like this author) trying it on.

As the former Lord Mayor of London Peter Levene said recently, “If two people applied for a job who were equal and one had been to business school and the other one had had five years’ working experience – I would take the one with work experience every day.”

Business aside, much of the rest of the book is concerned with LCoS’s foray into politics and his troubles with the media.

Some of this makes for good reading, if only to show you how terrible most people working in those two areas of life are. You also get some interesting insights into the behind the scenes of Brexit campaigning.

On that point, one thing that I remember finding weird when reading IG founder Stuart Wheeler’s autobiography a couple of years ago was the omission of LCoS.

Wheeler and LCoS have both been major Conservative Party donors and were also on the board of the Vote Leave campaign. Given they also made their money in what is a rather niche industry, you’d think they’d mention each other at some point. But LCoS does the same thing and there is no mention of Wheeler at all.

Finally, no review of this book can avoid mentioning the huge chunk that is aimed at discussing the ‘incident’ that took place a decade ago.

For those not in the know, in 2012 two undercover journalists filmed LCoS ‘selling’ favours to wealthy Conservative Party donors. Except that’s not what happened. The journalists clipped the video and edited it to make LCoS look bad.

I was only tangentially aware of this and was quite shocked at the real details of the story. That being the case, it’s pretty great reading someone dunking on the two journalists for about 100 pages.

Some people might say it’s over the top but I don’t think so. Deliberately lying about someone and dragging their name through the mud is a nasty thing to do in general. It is a thousand times worse if you are doing it in the national press. What’s depressing is that both of the journalists in question are still working and that their lies, when exposed, were barely covered by the press.

What the incident shows is a sadly widespread belief among journalists that they have to ‘hold people in power to account’ (translation: push whatever narrative they think is correct), as opposed to reporting facts. This then leads them to malign people or totally misrepresent what they’ve said in pursuit of that goal. As a simple example of this, watch this interview with Stuart Wheeler. Listen to what he actually says, then (i) look at the video title and (ii) listen to the questioning he is subject to. Do you get the impression Channel 4 is trying to find out facts or just push a narrative? The answer is obvious.

Unfortunately this isn’t going away and companies should understand this before engaging with the press. You can even take a Machiavellian approach and use it to your advantage. But that’s a post for another time.

Have a good week everybody.

Stuff that happened: